The Africa Bypass, and the Canal of the Pharaohs

The Ever Given is gone, out of the way and out of our minds. The Suez Canal remains, and will always remain, for simple geographical reasons. I’ll explore the reasons why that ~90 mile stretch of land between the Red Sea and Mediterranean1 will remain important for as long as humans trade by boat. However, this isn’t just a geographical explainer, but a historical explainer, too. The land between Suez and the Bitter Lakes weaves together the ancient Egyptians, Napoleon, and the British Empire’s triumph, and downfall. Lands last longer than empires, as we shall see.

But first: why is the Suez Canal so important? Note the map below. If you’re coming from India, China or South East Asia with goods to trade, as you approach the Horn of Africa (pic 1) you’ve got to sail a long way to get to Europe and beyond (see picture 2)

Horn of Africa in the bottom right.

(2)

You’ve got to, in other words, sail around the whole of Africa (around the Cape of Good Hope) in order to reach the European and American markets.

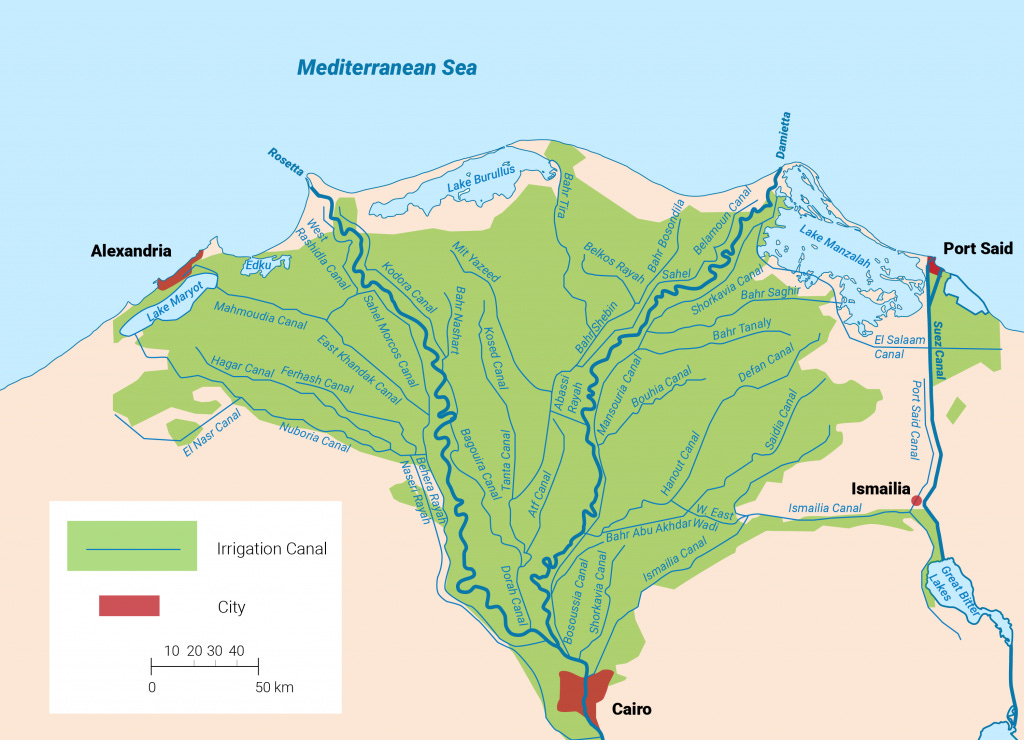

Now revisit picture 1, and note the Suez Canal. What a pristine shortcut! Why wouldn’t you consider cutting through Suez? Humans of different epochs have all reached this same conclusion. The ancient Egyptians were the first to consider the trade advantages of connecting their adjoining northern and eastern seas, and this trade generated vital revenue. Records are dusty, but the first canal was dug in roughly 1850BC, not where it is today on that stretch of land between the Red Sea and the Mediterranean. Instead, it connected the Nile Delta with the Red Sea, similar to the ‘Ismailia’ canal seen in (3). It had an epic name: Canal of the Pharaohs. That canal was expanded by the Persians, the Greeks and then the Romans.

(3)

The ancient canal relied on the water volume of the Nile, and of the Red Sea. When the Nile flooded every year, the Canal of the Pharaohs reopened for business. As the earth entered a drier period:

“the Red Sea receded... and the ancient canal, clogged with silt, faded into the desert.”2

In other words, the Suez Canal has been around for long enough to have been affected by climate change.

“On pourrait construire un canal?”

After its last recorded use,3 the canal’s ruins lay dormant for over a thousand years. Who considered rebuilding the Suez Canal? Napoleon Bonaparte. At this time the Corsican was not yet Emperor of France, nor was he even in France. He had embarked on a remarkable journey to conquer Egypt. As Paul Strathern explains, this was an act by the ruling council of France to put the ‘Liberator of Italy’ as far away from power as possible.4

The idea to take Egypt, and its strategic trading position, did not originate with Napoleon. Rather, the consideration of Suez as a nexus of east-west trade had been floated since the mid-1700s as a means of undermining the British and Dutch East India companies. It just took someone with Napoleon's monumental ego to actually attempt it.5 And so, there Napoleon stood, towards the end of his first year of conquest, in Suez. Despite almost drowning looking for the ancient canal site, he succeeded. Napoleon discovered the ruins of the canal running from Suez to the Red Sea, and from the Bitter Lakes to Suez. What’s more, Napoleon suggested the reroute from west (and the Nile Delta) to north (and the Mediterranean sea).6 One could claim, then, that Napoleon was the godfather of the modern Suez Canal.

Fundamentally, Napoleon’s engineers did not construct the route because of a miscalculation - that the water level of the Red Sea was thirty-three feet higher than that of the Mediterranean; they worried that the land would be flooded, and spoiled.7 It would not be until 1854 that fellow Frenchman Ferdinand de Lesseps would gain permission to attempt the canal again. He would succeed, following the route suggested by Napoleon.

The Canal, Colonisation and Decolonisation

The Suez Canal was commissioned by Egypt to decrease its reliance on the Ottoman Empire (which it, strictly speaking, was a part of). Ironically, through building the Suez Canal, Egypt would become a British colony. Eugene Rogan, author of The Arabs: A History writes:

“The single greatest threat to the independence of the Middle East was not the armies of Europe but its banks.”8

There were two main strategies for gaining power through finance: European governments demanding compensation for their citizens investments in foreign companies, and loans with high interest rates lent by European banks. Eventually, Egypt declared bankruptcy (in 1876) and its shares in the Suez Canal Company were sold to the British government. Originally, the Suez Canal was being considered as a means to undercut British trade, by the French. The British crushed that plan by exercising control over the Suez Canal. Yet more intrigue followed before Britain ruled Egypt, but first they ‘ruled’ the canal, for the sake of their commercial interests.

The Suez Canal was important enough to draw the 18th century superpowers- Britain and France- to the Red Sea shore. Britain did not want to rule Egypt,9 it simply had to protect its trade interests, and the Africa-bypassing canal was vital to that end.

The British Empire in 1882 could throw its weight around. It would send its warships to intimidate another state if it so pleased, and it would conquer a country if it was beneficial to trade. The British Empire of 1956 had the same mentality, exercised in a different world, and with diminished advantage. Britain was poor from World War Two, and no longer wielded significant technological advantage. Egypt had been formally independent since 1954, but British troops remained in Suez to protect, as ever, their commercial interests. When the socialist president of Egypt, Gamal Abdul Nasser, nationalised the Suez Canal, Britain once again reacted with force.

Britain planned for Israel to invade from the north, with Britain and France joining shortly thereafter in “reaction” to the outbreak of war. Britain and France bombed Egyptian military bases and landed paratroopers along the Suez Canal. American president Eisenhower was furious, asserting that imperial interests had no place during the cold war, and that such aggression would give the USSR a pretext to expand their influence, as protectors of the terrorised nations. The USA threatened no less than to expel Britain and France from NATO, and to weaken the British economy through selling British Sterling bonds. Both nations had to back down, and the post-WW2 order was established; if anyone was in charge, it was the Americans, and it certainly was not the British.

A lot changes over the course of these histories. Simple row boats would have coursed down the Canal of the Pharaohs, Steamships would have navigated the isthmus in the 19th century, and today 4,000-5000lb container ships traverse the canal. The ancient Egyptians are long gone, Napoleonic France is a distant memory, and the British Empire, too, has faded. What remains is the geography of the planet. Bypassing Africa by sea will always be attractive, for as long as trade runs from east-west by boat. This is the beautiful thing about geography; we don’t know what nations will exist in the next 500, 1000, 2000 years, but if the peoples along the Nile have robust military and diplomatic defences, then they will control the Suez Canal. If, however, a more powerful nation can control the Suez with impunity, then they will, because they’ll exercise power over 12% of world trade, and collect custom duty on it, too.

It is often claimed that humans are unique because we control and manipulate the land. What we learn through the history of the Suez Canal is that the land also controls us.

♠ Please help me grow Spade ♠! If you know someone who would enjoy this piece and perhaps subscribe, then please send it on.

Jack

x

Picture credits:

https://www.google.co.uk/maps (with my masterful(!) MS paint edits)

The Africa Bypass, and the Canal of the Pharaohs

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Suez-Canal/History

https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2021/03/26/suez-canal-history/

“On pourrait construire un canal?”

Paul Strathern, Napoleon in Egypt, Random House: London, 2007.

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Suez-Canal/History

Suez Canal, Colonisation and Decolonisation

Eugene Rogan, The Arabs: A History, Basic Books: 2017, Chapters 5 & 10.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-56559073

All articles accessed in early April.

Otherwise called an isthmus, and which I might boldly call an isthmus myself, in the rest of the article...

Ishaan Tharoor, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2021/03/26/suez-canal-history/

By use here, I refer to the Abbasid’s destruction of the canal, for ‘military reasons’. Not much of a use at all, really, but still the last mention, at 775AD.

(Strathern, 30 & 47) With 50,000 men and 180 ships at his disposal, this was an extreme measure to ‘handle’ General Bonaparte. However, with this comment I cease the background. If it interests you, too, then please read Strathern’s book, cited in the bibliography

Read the book below about this, if interested. The French invasion of Egypt under Napoleon was madness, fascinating madness. The first conflict between Napoleon and Nelson occurs in Egypt, too.

Strathern, Napoleon in Egypt, Random House: London, 2007: 269.

Ibid, 270. [same source as above]

Eugene Rogan, The Arabs: A History, Basic Books: 2017, 147.

Ibid, 178.